АО стандардна хирургија: фиксација вијака за измењене преломе таларног врата

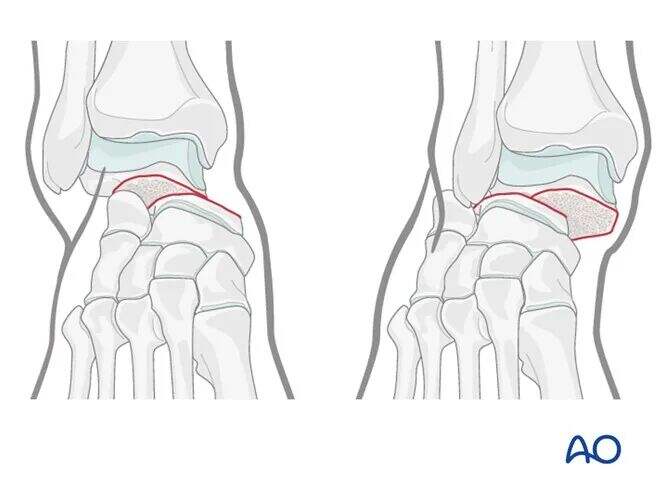

Анатомија

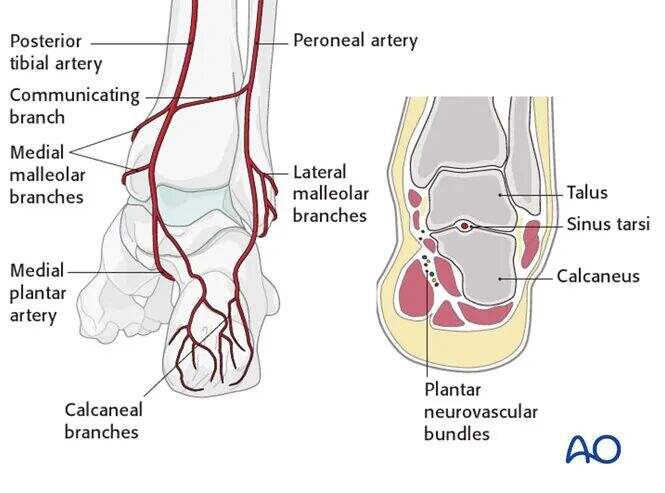

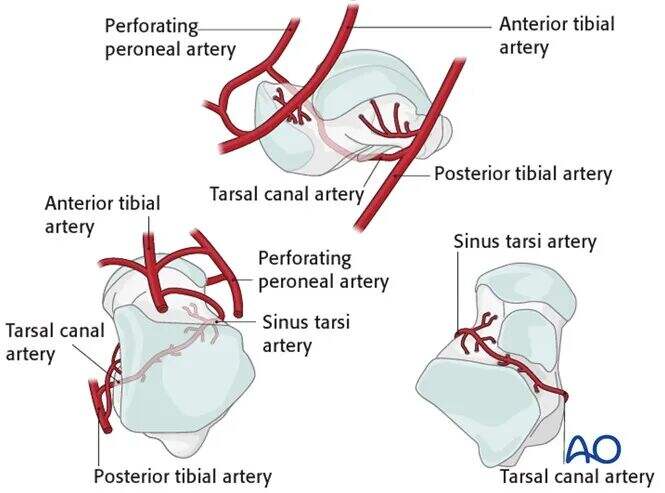

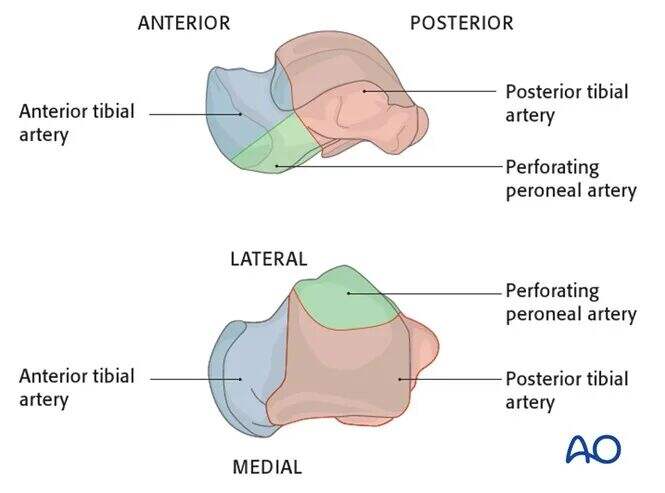

Добављање крви у талус је озбиљно угрожено у случају фрактура-изложења. Задња тибијална артерија се раздваја медијално, задња артерија предње, а перонејална артерија бочна. Ове судове се анастомозирају кроз васкуларну мрежу у тарсалном каналу.

Дельтаидна грана задње тибијалне артерије мора бити сачувана. То је критична улазна тачка за снабдевање крвљу медијалног таласа, због чега медијална малеоларна остеотомија може успешно заштитити снабдевање таларном крвљу.

● Дельтаоидна грана је од кључног значаја за снабдевање крвљу средњег талара и тела талара.

● Пологе артерије dorsalis pedis снабдевају главу талара и већину врата.

● Артерија тарсалног канала, која потиче из грана задње тибијалне артерије, снабдева већину тела талара.

● Донос перонеалне артерије са бочне стране је минималан.

Одлука о третману

Ако се таларски слом врата није изместио и све површине зглобова су добро израмњене, разумна је опција неоперативно лечење.

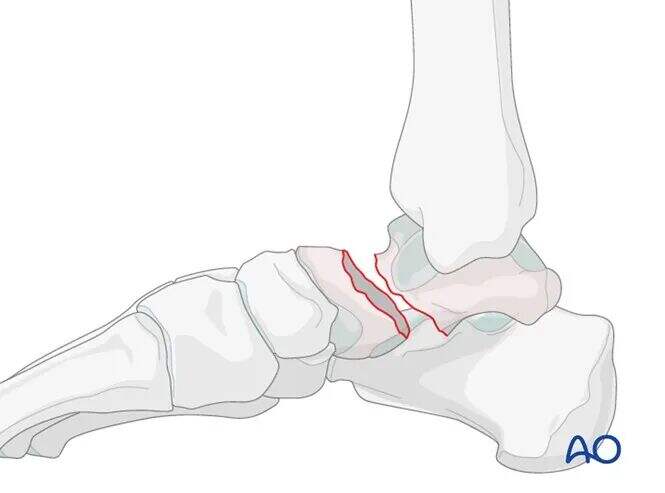

Ако се фрактура измести, она је често повезана са другим повредама задње ноге, што захтева даљњу процену и формулисање других плана лечења.

Непромењени фрактури могу захтевати само обичне рентгенске снимке, али овај сценарио је реткост; већина талара фрактура врата имају барем неки степен измештања.

ЦТ скенирање је непроцењиво важно када постоји сумња у измештање фрактуре или када је потребно дебридирање субталарног зглоба. Са повећањем тежине повреде, веће померање обично подразумева озбиљније оштећење остеохондра субталарних и тибиоталарних зглобова. Такве фрактуре често захтевају хируршко дебридирање и фиксацију.

Преглед затвореног смањења

За измењене таларове фрактуре врата са лошим условима меких ткива, треба покушати затворену редукцију кад год је то могуће. То је зато што неисправљена деформација може довести до оштећења меких ткива и коже. Ако су мека ткива у добром стању и ако сустав није изложен, хируршка интервенција се може одложити.

Још један важан разлог за рано редукцију прелома таларовог врата је критична важност снабдевања крвљу таларовог врата и тела. Што је више времена прекретање или дислокација фрагмената, то је више угрожено већ сложено снабдевање крвљу.

Међутим, тешкоћа затворено редукције значајно се повећава са тежином слома таларовог врата. Успешна стопа затворена редукције за Хокинсове фрактуре типа II је само 30% -60%. Осим тога, затворена редукција не мора да постигне анатомску редукцију; њен циљ је да заштити мека ткива током периода пре коначне неге.

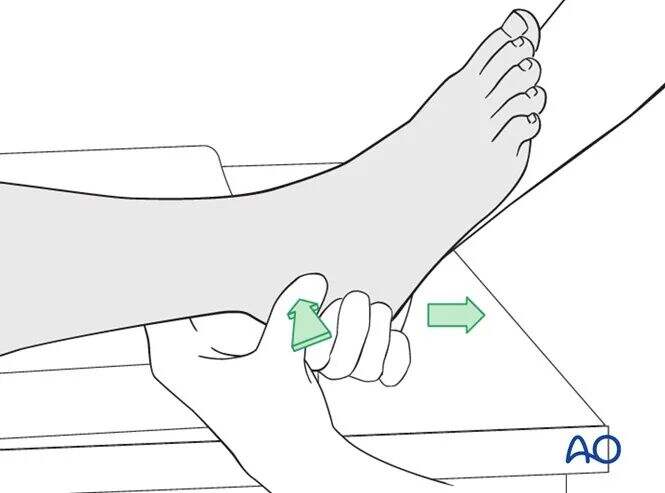

Техника затворена редукције

Повређена страна може се идентификовати посматрањем отечености и деформације стопала. Упоређивање са нормалним контралатералним стопалом пацијента помаже у разумевању њихове индивидуалне анатомије.

Тело талара обично остаје релативно фиксирано на тибији, док таларска глава и калканеус сублукс медијално или бочно.

Тракција

Продочна тракција у комбинацији са обрном деформационе снаге може помоћи у маневру смањења.

Ако је редукција успешна, нормална анатомија се враћа. Деформишућа сила може бити или медијална или латерална, у зависности од правца померања прелома.

Обично, након успешног смањења Хокинсовог типа II таларовог слома врата, нормална анатомија стопала се обнавља. Накнадна проценка захтева иммобилизацију лима и рентгенску процену.

Не препоручују се вишекратни покушаји затворено редукције како би се избегло даље оштећење меких ткива.

Преглед отвореног редукције

Хокинсова фрактура таларовог врата типа III је генерално нередуцибилна затвореном методом, али се ипак треба покушати (успешна стопа < 25%). Принципи управљања Хокинсовим фрактурама типа IV слични су онима типа III.

Хокинсове фрактуре типа II су мање често отворене фрактуре, али 50% Хокинсових фрактура типа III представљају отворене повреде.

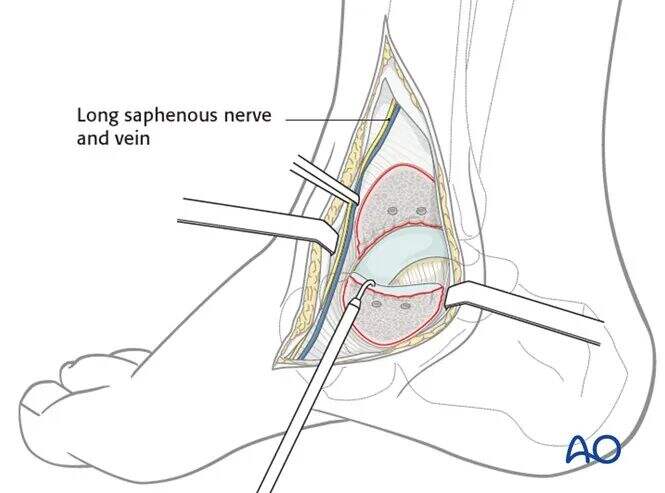

Експозиција

За све таларе фрактуре врата које захтевају операцију, комбинација антеромедијалног и антеролатералног приступа је оптимална. Ови два реза обезбеђују адекватну визуелизацију за редукцију и фиксацију.

Помоћ током отвореног смањења укључују се вођске жице, спољни фиксатори, мали дистрактори или ламинарни раширитељи; фар лампа побољшава визуелизацију, а Ц-арм (интензифичери слике) води смањење овог сложеног кршења.

Ако се смањење не може постићи стандардним комбинованим антеромедијалним и антеролатералним приступама, медијална малеоларна остеотомија је најчешће коришћено решење. Модификовани нагини бочни рез је такође опција.

Медијална малеоларна остеотомија потребно је продужити антеромедијални рез како би се омогућио приступ за остеотомију. Мора се водити рачуна да се са остеотомизацијом одржава интегритет делтоидног лигамента како би се заштитио снабдевање крвљу таларног тела.

Отворено маневрирање смањења

Током процедуре, све мека ткива која се причвршћују за тело талара (изворе снабдевања крвљу) морају бити сачувана. Обично је неопходан приступ са двоструким резом.

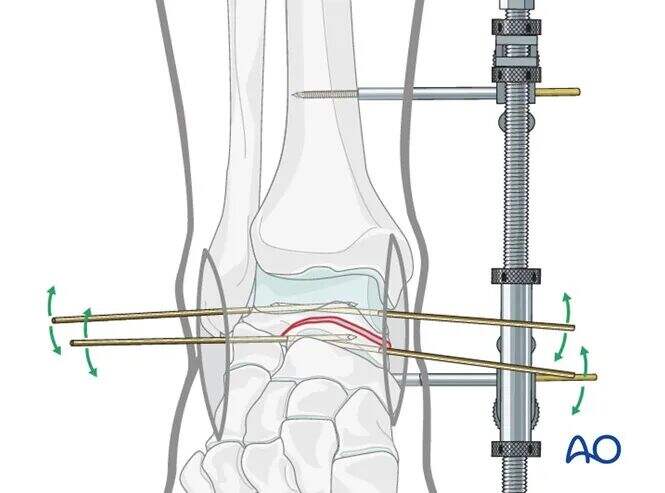

Ако комбиновани приступ и даље не успева да постигне редукцију, наставите следеће: прво користите периостеалне подизаче и вођске жице, затим нанесете спољни фиксатор и дистрактор, а на крају изведите медијалну малеоларну остеотомију (најинвазивнија, Сваки корак треба да се врши под вођством Ц-раме.

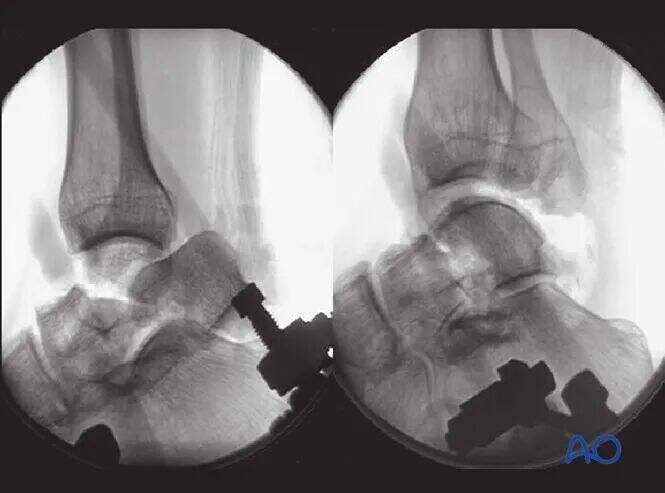

На илустрацији је приказана пацијент под општом анестезијом са потпуним опуштањем мишића. Медијални дистрактор се користи за постизање смањења фрактуре таларовог врата кроз тракцију, корекцију ротационих деформација и обнављање таларског тела у његову анатомску позицију.

Друга слика показује ефекат смањења таларовог врата са тибиоталарним зглобом који се држи у одвраћању.

Фиксација

Привремена фиксација

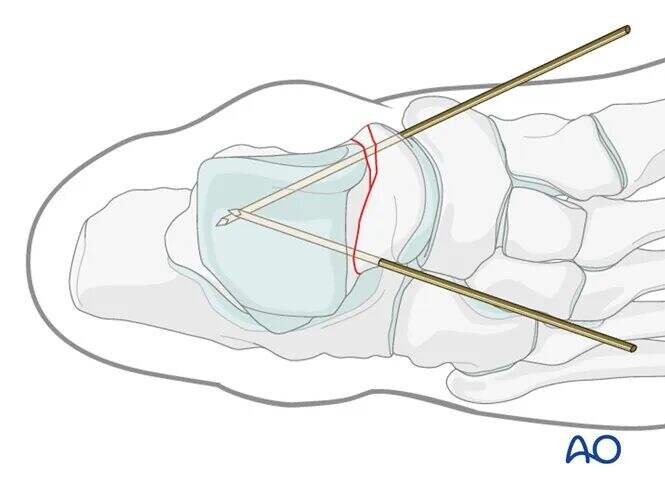

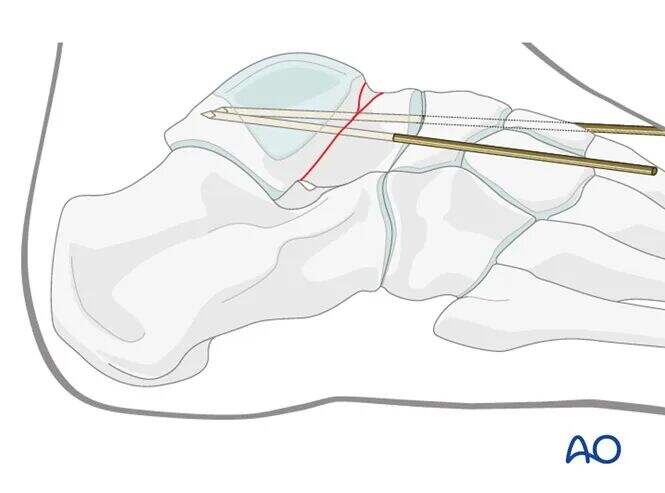

Страна страна: Киршнер жице (К-жице) помоћ у постизању привремене фиксације. Њихова поставка је од кључног значаја за коначно фиксацију вијака када се користе канулирани вијаци.

Бочни таларов врат обично није раздвојен; редукција се може постићи интердигитацијом фрагмената фрактуре. Фиксација вијака у компресијском режиму је погоднија бочно.

Средња страна:

Медијални таларов врат често има одређен степен скршћа. Редокација треба да се врши под вођством Ц-раме. За фиксацију треба користити потпуно затечен кортикални вит за позиционално фиксацију. Ако се користи лаг вит, затезање може изазвати измештај медијала и скраћење таларовог врата.

Медијални К-жице се обично најбоље постављају кроз медијални део таларске главе чворне хрскавице како би се омогућило следеће противпотање вијака.

Фиксација вијака

Када је К-провода постављање задовољавајуће и редукција је потврђена тачно са Ц-рука, канулирани вијаци могу бити устављени преко водича.

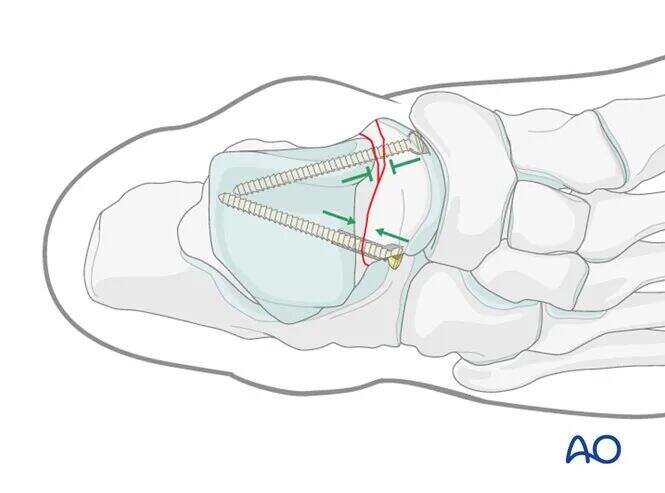

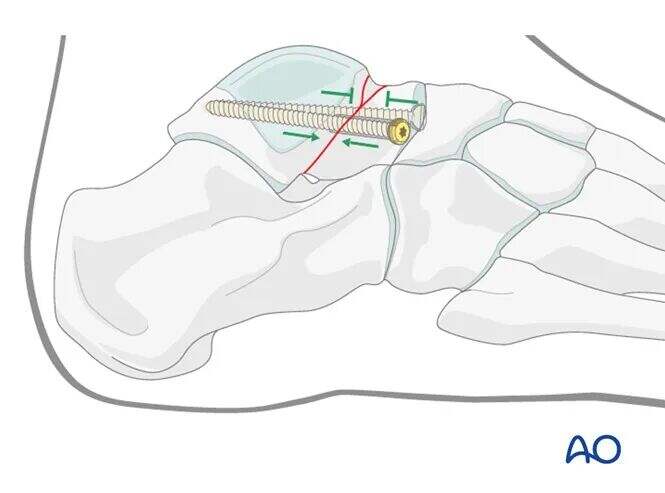

Због честа медијално кршење, треба избегавати лаг ефекат. Вице овде захтевају фиксацију без компресије (позиционалне вице). Глава вијака је обично противпоточена на медијалној ивици површине талонавикуларног зглоба.

Бочно, нема губитка костију и фрактура је стабилна кроз интердигитацију, што јој омогућава да издржи притисак. Оптимална метода фиксације је канулирани лаг вит. Вит треба да прође кроз косту латералног талара, а не кроз зглобну хрскавицу.

Ове вијаке не морају бити постављене паралелно, јер се њихови механизми разликују: бочна вијака обезбеђује компресију, док медијална вијака служи само за позиционално фиксацију.

Завршење фиксације

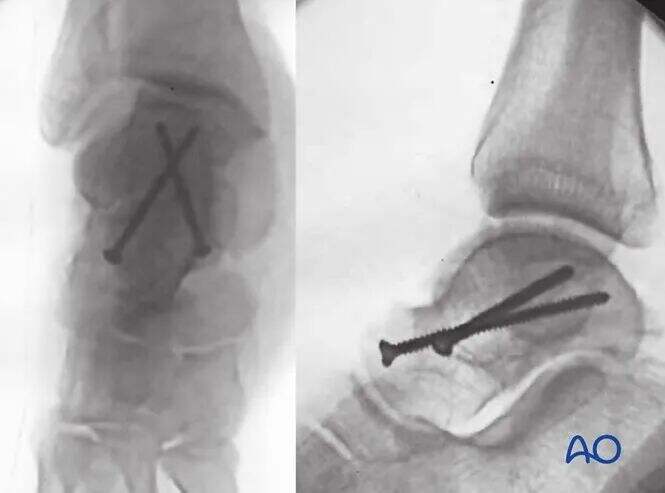

Интраоперативне проверке Ц-рама осигурају прецизно смањење свих површина таларних зглобова. Виде канала на глезеницу и стопалу потврђују задовољавајуће смањење и фиксацију фрактуре таларовог врата.

Илустрација показује стабилну фиксацију Хокинсовог прелома типа II. Обратите пажњу на непаралелно постављање вијака: компресијски вијак бочно и позициони вијак медијално.

Искусни хирурзи понекад користе технику фиксације вијака од задње до предње стране.

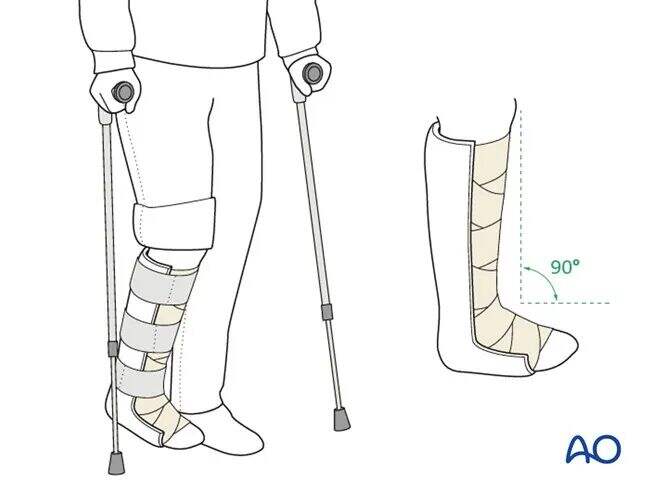

Постепене терапије

● Након операције, ногу треба зауставити у позадинској шини у неутралном положају. Препоручује се рана вежба мобилизације за глезенице и сублатарне зглобове.

● 6 недеља након операције је забрањено носити тежину. Последичне рентгенске снимке се узимају у 2 и 6 недеља.

● Вежбе за мобилизацију зглобова треба да се започну чим пацијент толерише, са циљем да се врати добар опсег кретања.

● Рентгенски зраци у 6. недељи потврђују заздрављење прелома. Када се кости уједине, може се почети постепено вежбање са тежином.

● Пацијенти са латарским фрактурама врата не би требало да почињу да носе тежине док је на месту фрактуре бол.